This page is an excerpt from Issue 1 / Chapter 4.

Apocalypse Nord

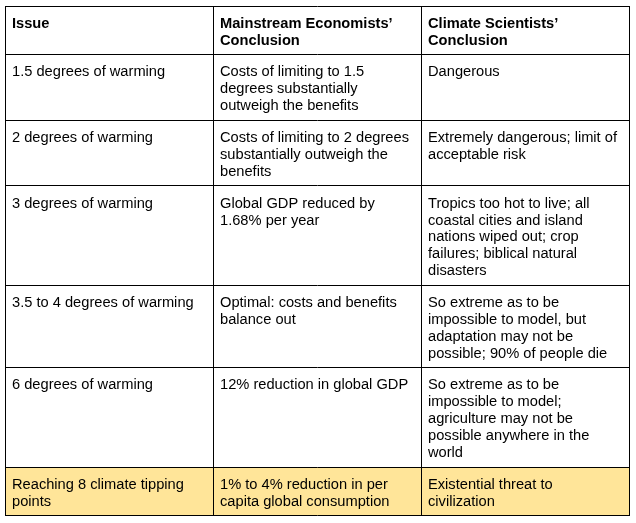

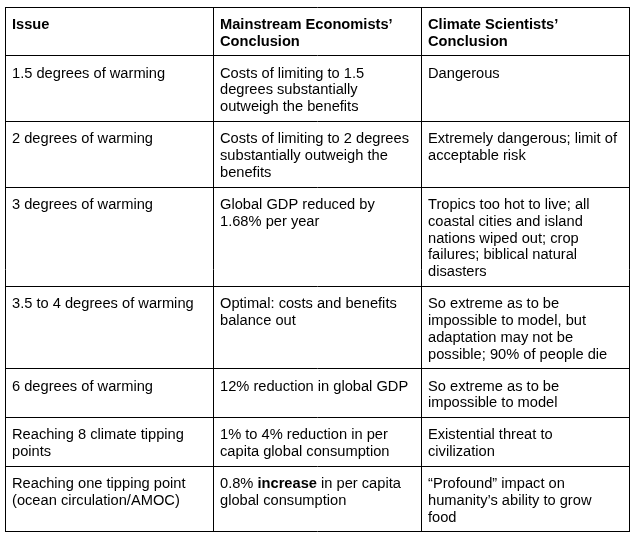

This section is a side-by-side comparison of what mainstream economists versus climate scientists say about climate change. In this section, we use the generally accepted shorthand for warming: e.g., “2 degrees of warming” is shorthand for an average global temperature increase 2 degrees higher than that of the preindustrial world (in 2100, unless otherwise specified).

The founder and leading exponent of climate economics is Yale economist William Nordhaus, the first economist to apply the principles of mainstream economics to climate change. It is no exaggeration to say that Nordhaus is the most important and influential climate economist in the world, and among the most important and influential economists, period. Nordhaus is co-author of the most-read introductory economics textbook, has taught society’s future elites as an Ivy League professor since 1967, and won the 2018 Nobel Prize for Economics.

Nordhaus won the Nobel Prize for developing the so-called Integrated Assessment Model (IAM), a process for modeling the economic impacts of climate change that allows for a comparison of the costs of implementing green policy today versus the benefits of preventing the worst effects of climate change for future generations. IAMs have three components. First, an equation calculating economic growth as though there were no climate change. Nordhaus’s models assume 1.9 to 2.1% growth every year. At 2% annual growth, the global economy would approximately double every 36 years and would approximately quadruple by 2100. Second, a damage function: a mathematical equation that estimates the economic costs of climate change to the future economy. Third, an abatement cost function, a mathematical equation that estimates the costs to today’s economy of eliminating the use of fossil fuels.

Nordhaus and other mainstream economists make climate policy recommendations by plugging different variables (future economic growth rates, cost of adapting to climate change, estimates of how quickly the world will warm, etc) into an IAM, then comparing results. The crux of mainstream climate economists’ argument is this: it makes no sense to rapidly phase out fossil fuel use if the costs of doing so today (the abatement cost function) is larger than the costs imposed by climate change in the future (the damage function). Policy makers should aim for an “optimal” warming, wherein fossil fuels are phased out slowly enough that the abatement cost function (the costs of phasing out fossil fuels) will be equal to the damage function (the costs of dealing with climate change in the future).

For example, at 3 degrees of warming, Nordhaus calculates that the damages to the future global economy would only be 1.62% of global output per year. Per Nordhaus’s modeling, such tiny damages are substantially smaller than the abatement cost: in other words, the cost of limiting climate change to 3 degrees is significantly higher than the benefits of doing so. According to these models, limiting warming to 1.5 or 2 degrees is patently absurd: the costs to society of phasing out fossil fuels quickly enough to meet these goals are mammoth compared to the future benefits of doing so. Nordhaus’s argument boils down to: why should people alive today sacrifice so much for a tiny benefit – a tiny benefit that most of us will not even live to see?

Climate scientists, however, consider 2 degrees to be so dangerous that it is the absolute maximum amount of warming we can possibly accept. 1.5 degrees of warming is substantially less dangerous than 2 degrees; 2 degrees is extremely dangerous (as summarized with exhaustive citations at earth.org):

Heatwaves will become more common, more intense, and longer-lasting in a 2C warmer world. Research suggests that the probability of experiencing a heatwave like the one that affected Europe in 2003, causing over 30,000 deaths, will increase from once every 100 years to once every 4 years under 2C of warming.

Regions already prone to high temperatures, such as the Middle East and North Africa, will experience “super heatwaves” with temperatures exceeding 50C (122F). This will make some areas potentially uninhabitable…

Droughts will become more frequent and more severe in many parts of the world. The IPCC projects that the area of global land affected by drought disasters will increase by 50% for 2C compared to 1.5C…Besides affecting water resources, intense and prolonged droughts will decimate food crops and cause high rates of livestock deaths, leading to food insecurity.

While some areas will get drier, others will get more flooded. With 2C of warming, the IPCC estimates that the global population exposed to river flooding will be up to 170% higher compared to a 1.5C scenario…This increase in extreme rainfall events will mean more flash floods and urban flooding…

[T]he proportion of Category 4 and 5 hurricanes will increase by 13% and the average intensity by 5%. [ ] More powerful storms will bring stronger winds, more rainfall and higher storm surges, endangering coastal communities and infrastructure…

[M]ean sea level is projected to rise by 0.46-0.99 meters (1.51-3.25 feet) by 2100 [leading to a] climate refugee crisis driven by the displacement of millions of people living in coastal areas…

Studies suggest that 99% of coral reefs will be lost…

The rate of species extinctions is expected to accelerate, with one study projecting that 18% of insects, 16% of plants, and 8% of vertebrates will lose over half their climatically determined geographic range with 2C of warming.

For 3 degrees’ increase, climate scientists model that much of the tropics will become “too hot to live,” oceans will rise enough to wipe out all island nations and coastal cities (including economic powerhouses like New York, London, Hong Kong, and Shanghai), crop failures will dramatically increase, and natural disasters like extreme rainfall and flooding, droughts, wildfires, and hurricanes will increase in frequency and severity.

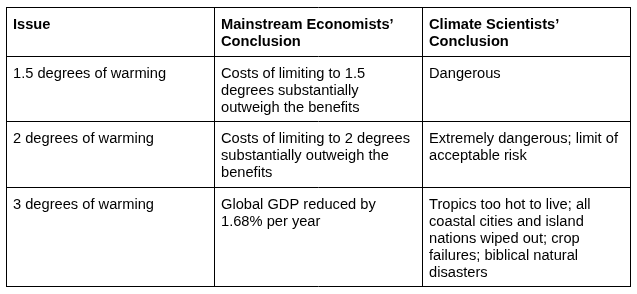

Because so many numbers are being thrown around, let’s use a table to keep track:

You may be wondering: if the economy of every single coastal city, island nation, and tropical region on earth is wiped out; if all those people are displaced from their homes and have nowhere to go; if crop failures and indefatigable natural disasters become commonplace – how can this only lead to a 1.62% dent in global output? Clearly, Nordhaus’s economic models are wrong.

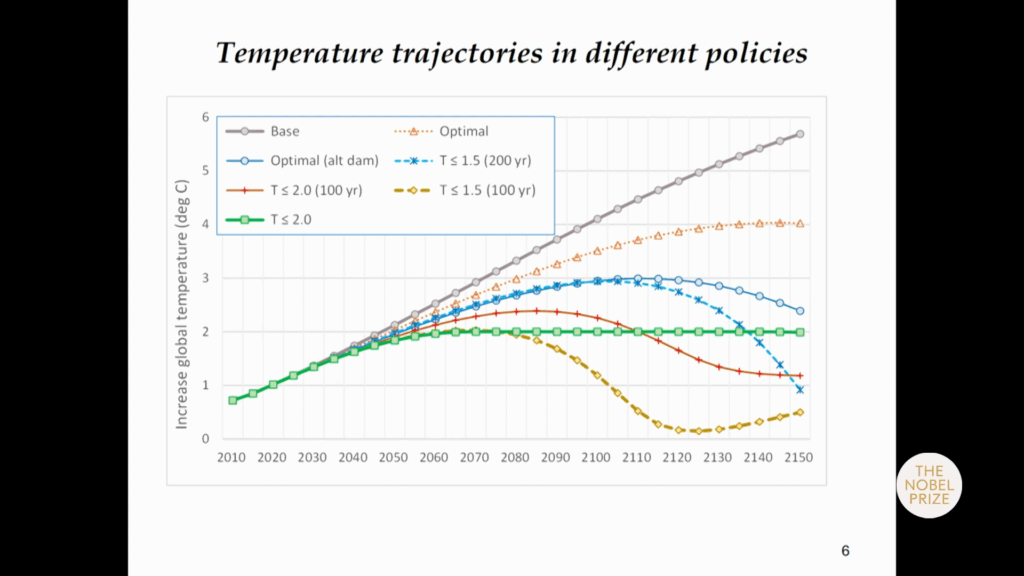

It gets worse. According to Nordhaus’s calculations, the “optimal” warming is 3.5 degrees by 2100, plateauing at 4 degrees thereafter. Here is Nordhaus’s figure from his 2018 Nobel Prize lecture (slide 6):

Per Nordhaus’s calculations, the sacrifices that need to be made today to limit climate change to 3.5 to 4 degrees balance out with the benefits that accrue to future generations.

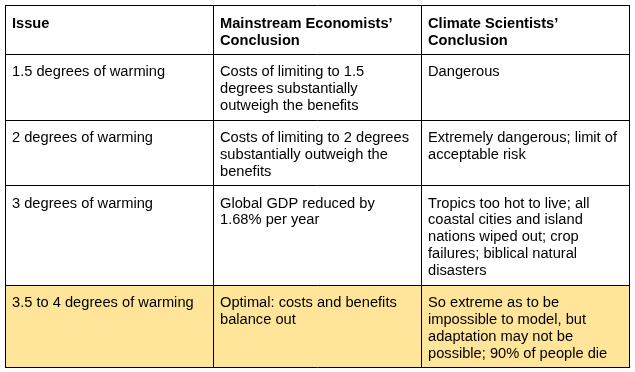

What do climate scientists think about Nordhaus’s recommendation that 3.5 to 4 degrees is “optimal”? In fact, climate scientists do not even model out past 3 degrees. That’s because the rate of climatic change becomes so extreme that it is impossible to make models or estimates. Climate models are built on data, and data can only be obtained from real-world measurements. Earth has never warmed as quickly as it is warming now, but climate scientists have nonetheless had remarkable success in making accurate climate change predictions by extrapolating from data that do exist. However, warming by 3.5 or 4 degrees is so far beyond the existing dataset that climate scientists do not think it is possible to make predictions with any degree of accuracy. This begs the question: if there are no models for what the climate will look like at 3.5 to 4 degrees of warming, how can Nordhaus and other mainstream economists so confidently predict the impact of 3.5 to 4 degrees of warming on the economy?

While acknowledging the limitations of data and modeling at such extreme amounts of warming, climate scientists have nonetheless speculated about what 4 degrees of warming could look like. When asked to make predictions for 4 degrees of warming by the World Bank, climate scientists argued that accurate prediction was impossible but warned that “there is also no certainty that adaptation to a 4°C world is possible…4°C warming simply must not be allowed to occur.” When asked directly about 4 degrees of warming, one climate scientist said “something like 10 percent of the planet’s population — around half a billion people — will survive if global temperatures rise by 4 C”, and another demurred that “it’s difficult to see how we could accommodate a billion people or even half of that.”

Let’s update the table (new cells in yellow):

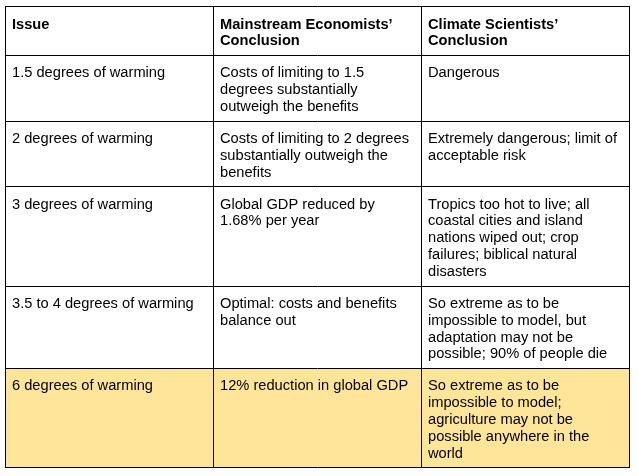

Nordhaus estimated that at 6 degrees of warming, global GDP would be reduced by only 8.5% (an estimate he later revised upward to 12%). For climate scientists, 6 degrees of warming would be so extreme that no climate scientist has even modeled it. In the final chapter of Six Degrees (republished in 2020 under the name Our Final Warning), author Mark Lynas attempted to envision in layperson’s terms what the world would look like at 6 degrees of warming. However, Lynas did not find any studies modeling to 6 degrees because there is no way to model such extreme changes. Since no climate models were available, Lynas instead turned to paleoclimatology, a field of geology that uses fossil and geological evidence to reconstruct Earth’s climate before recorded history. Based on evidence from previous periods when Earth was this hot, Lynas speculated that agriculture would be impossible for nearly all of the world, as even Canada and Siberia would be too hot to support farming. (Here are climate scientists grappling with the lack of peer-reviewed studies anticipating catastrophic climate change.)

Another update to our table:

Tipping points, such as the melting of polar ice and the conversion of the Amazon to savannah, are areas of special concern because they have the possibility to abruptly – and irreversibly – lead to an acceleration of climate change. For example, polar ice reflects a great deal of the sun’s heat back into outer space. If the planet warmed enough to wipe out polar ice, climate change would suddenly and irreversibly accelerate because all that extra heat from the sun would no longer be reflected. Climate scientists have identified eight terrifying tipping points and believe that breaching them would be “an existential threat to civilization”. Mainstream economists using IAMs calculated that if humanity passed all eight tipping points identified by climate scientists, per capita global consumption would fall by between 1 and 4%.

Perhaps the most extreme example of the discrepancy between the predictions of mainstream economists and climate scientists is found in the modeling of one tipping point: the slowdown of the massive Atlantic Ocean current (Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, or AMOC) that keeps Europe and North America warm and cools the tropics by circulating huge amounts of warm water north and cool water south. In a paper reviewed by Nordhaus, economists used IAMs to estimate that a slowdown of the AMOC would have a small but beneficial impact on global GDP, and the greater the slowdown, the greater the benefit: a small slowdown would increase global per capita income 0.2 to 0.3%, whereas a near-shutdown would increase global per capita income by 0.8%. The conclusions of climate scientists could not be more different. Climate scientists have estimated that the slowdown of the AMOC would “destabilize the West African monsoon, triggering drought in Africa’s Sahel regions[,] dry the Amazon, disrupt the East Asian monsoon and cause heat to build up in the Southern Ocean, which could accelerate Antarctic ice loss.” It would also lead to lower agricultural productivity in Europe. Rather than beneficial impacts on the global economy, a weakened AMOC would lead to “profound consequences for global food security” due to substantial new challenges of growing food in Europe, Africa, South America, and Asia. Another climate scientist described an AMOC collapse as a “going-out-of-business scenario for European agriculture…You cannot adapt to this.”

We could go on with more examples, but this selection should give you an idea of the gravity of the difference in thinking between mainstream economists and climate scientists – as well as the importance of choosing whom we trust to design climate change policy. The differences between the two camps could scarcely be more extreme, and we will have dramatically different futures depending on whose advice we choose to heed.

How can mainstream economists predict minor dents in global GDP when climate scientists see existential threats to civilization itself? For starters, IAMs literally assume that catastrophes like famines, wars over dwindling resources, or areas of the earth being so hot during summer that they are uninhabitable, can’t happen. In the words of heterodox economists (including Joseph Stiglitz, winner of the 2001 Nobel Prize for Economics), “potentially catastrophic risks are in large measure assumed away in the IAMs”. Heterodox MIT economist Robert Pindyck says the same:

Another major problem with using IAMs to assess climate change policy is that the models ignore the possibility of a catastrophic climate outcome…The bottom line here is that the damage functions used in most IAMs are completely made up, with no theoretical or empirical foundation…IAM-based analysis suggests a level of knowledge and precision that is nonexistent, and allows the modeler to obtain almost any desired result because key inputs can be chosen arbitrarily.

Lest you think these heterodox economists are being unfair, listen to Nordhaus in his own words a year after winning the Nobel Prize, in 2019: “there is at this point no serious evidence” that catastrophic outcomes are possible. No serious evidence? In 2019? It is no exaggeration that mainstream economists are climate change deniers: you can only believe there is no serious evidence of catastrophic outcomes if you disregard climate science itself.

To understand the folly of IAMs better, let’s look at two examples of potential catastrophes that IAMs “assume away.” As explained by climate scientists, IAMs assume no migration: the world’s population distribution in 2100 is assumed to be the same as the population today (emphasis added):

changes in climate hazards can trigger human migration across different regions of the world, which in turn will have effects on land use, water availability, deforestation, desertification, and so on. Also, climate change may eventually make certain areas of the world hostile living places based on temperature rises leading to falling economic output, population decline, social inequality and political crises. However, these complex feedbacks are not adequately expressed in IAMs…population distribution and population density projections from current IAMs are exactly the same for a scenario with sustainable development and a scenario with fossil-fuel intensive development. This is obviously implausible

Total desertification of the Sahel, leading to tens of millions of climate refugees? Not accounted for in IAMs, which assume no net migration out of the Sahel for any reason. Sea level rise swallowing all coastal cities and island nations, displacing billions of people on every continent? Not accounted for in the IAMs, which assume no net migration for any reason. The displacement of 400 million people in the North China Plain as heat waves make the area literally too hot to inhabit? Not accounted for in IAMs, which assume no net migration for any reason. The displacement of up to 3.5 billion people, as much of India, and parts of Nigeria, Sudan, Indonesia, and Pakistan become too hot to inhabit? Not accounted for in IAMs, which assume no net migration for any reason.

In other words, IAMs can, in part, reach fantastically optimistic climate projections because they assume that famines and other disasters don’t happen, and that people can continue living in places that are too hot for human habitation or have been literally swallowed by the sea.

But even these assumptions might seem reasonable alongside the assumption that people don’t need food. Nordhaus has assumed that any economic activity that occurs indoors in “carefully controlled environments” – i.e. with the benefit of modern heating and air conditioning – will be unaffected by climate change. This includes “manufacturing, mining, transportation, communication, finance, insurance, real estate, trade, private sector services, and government services.” Leaving aside the robust research indicating heat does negatively impact supposedly climate-proof sectors, and leaving aside that stoppages to manufacturing and other supposedly climate-proof, air-conditioned processes are already occurring due to extreme heat, this logic literally says that because the market value of economic activity that occurs outside accounts for a small amount of our economy, the economic impacts of climate change are minimal. But one of the activities that must occur outdoors is agriculture(!). Obviously, if agriculture is severely impacted by climate change and there is not enough to eat, the rest of the economy can’t function. If you doubt this is his position, listen to Nordhaus in his own words responding to critics (emphasis added):

Ninety percent of U.S. economic activity has no interactions with the ecological changes [my critics are] concerned about. Agriculture, the part of the economy that is sensitive to climate change, accounts for just 3% of national output. That means there is no way to get a very large effect on the U.S. economy.

No way except for running out of food. This is how – as explained above – when climate scientists predict a “profound” impact on global food security and a “going-out-of-business scenario” for European agriculture if the AMOC shuts down, mainstream economists can predict a positive impact on human welfare.

Conclusion: those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it

The IAM concept is extraordinarily influential. The Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations all used IAMs as a guide to climate policy (instead of IAM they call it the “social cost of carbon”, but it’s the same thing). When researchers submitted freedom of information requests to UK pension funds, they found that 80% were basing investment decisions on IAMs. In covering Nordhaus’ Nobel Prize, the New York Times reported that “the [IAM] approach developed by Professor Nordhaus remains the industry standard.” Even the UN uses IAMs: heterodox economists point out (see footnote 4) that while the UN’s IPCC committee focused on climate science sounds alarm bells, IAMs are used for the IPCC policy recommendations. In other words, from governments to the UN to investors, the rich, powerful, and influential are relying on IAMs to understand climate change and decide how to deal with it.

But we have experience entrusting social policy to mainstream economists: commodity-driven development and structural adjustments were all based on mainstream economic models. They led to a catastrophic recession more severe and longer-lasting than the Great Depression, and people went hungry and died because of this folly. It certainly seems like we are heading toward climate catastrophe by following the policy recommendations of mainstream economists.

Finally, after all this discussion of IAMs and mainstream climate economics, we have uncovered the third major reason why the wealthy world cares so little about desertification: the powerful and influential are using IAMs to understand the problem, with all their totally unrealistic assumptions. The Sahel is expected to warm at 1.5 times the rate of the rest of the world. Though climate scientists can’t accurately model such extreme changes, mainstream economists’ “optimal” warming of 3.5 degrees Celsius at 2100 (and plateauing at 4 degrees thereafter) would almost certainly render the Sahel uninhabitable. This would turn tens of millions of people into climate refugees and pump an unfathomable amount of carbon into the atmosphere. But in an IAM model, nobody becomes a refugee (even if their region becomes unlivable), tipping points are assumed not to happen (or are estimated to have beneficial effects), and famines are assumed not to happen, despite the clear incompatibility of this warming and agriculture. In that mindset, it is no wonder desertification is ignored: no matter how many calculations are made and simulations run, a model that assumes famines, displacement, and tipping points don’t exist will never identify desertification as a problem.