By learning about the science of desertification, as well as the political and economic history of Cameroon, we have solved the two mysteries of Issue 1: what caused Lake Chad’s collapse? And why do so many Cameroonians lack access to clean drinking water?

____________________________________

Issue 1: Climate Change and Freshwater

Intro: Why did Lake Chad collapse and why are Cameroonians so thirsty?

Chapter 1: Desertification of the Sahel and Cameroon’s water infrastructure

Chapter 2: Cameroon gains “independence” from France

Chapter 3: Poverty, structural adjustments, and dictators

Chapter 4: The US New Deal’s Soil Conservation Service is a proven model

Bonus 1: More on Cameroon’s independence movement

Bonus 2: How did Ahidjo make himself a dictator?

Bonus 3: How did Biya take control from Ahidjo?

_____

Issue 1 is available in written and podcast format

__________

Cameroonians lack access to clean drinking water because Cameroon has been ruled by heartless dictators since 1960, neither of whom has ever shown any concern for the needs of ordinary Cameroonians. Even if there were a government responsive to its people’s needs, Cameroon has massive, unpayable debts. So much money is devoted to debt servicing that finding money for adequate water infrastructure is not realistic.

We also learned the roots of these political problems: Cameroon became a dictatorship thanks to the French colonial administration and their allies among Cameroon’s elite, and the debts are a result of forces – like commodity prices and interest rates – out of the control of any Cameroonian.

Meanwhile, Lake Chad lost 90% of its volume due to desertification of the Sahel and irresponsible diversions for agriculture. Desertification of the Sahel – itself a continent-wide ecological catastrophe – is caused by irresponsible agricultural practices. These irresponsible decisions are mostly forced by poverty, hunger, and desperation. In other words, desertification is the predictable result of the root causes of poverty: a broken development model, high levels of public debt, structural adjustments, and a kleptocratic government.

Yet for all we’ve learned, we are still left with two particularly disturbing questions. First, what does it mean that our worst fears of climate change are already happening? And second, why does the wealthy world not care about the Sahel? Land degradation accounts for a quarter of all of humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions. Stopping catastrophic climate change is impossible without solving the world’s land degradation crises. Even out of pure self-interest, we need to care about the Sahel. Why don’t we?

We promised in the introduction to Issue 1 that Cameroon and Lake Chad held crucial lessons for understanding the global relationship between climate change and freshwater. Finding answers to these disturbing questions will teach us much of what we need to know about climate change’s impact on freshwater resources. We’ll take both of these questions in turn, then conclude Issue 1 with a discussion of the policy approaches that can actually solve the Sahelian desertification crisis and climate change as a whole.

Climate change can’t be the problem because our worst fears of climate change are already happening

Before answering the first question – what does it mean that our worst fears of climate change are already occurring, but not due to climate change? – let’s review the ecological catastrophes mentioned in Issue 1. We listed the collapse of several freshwater ecosystems in the Issue 1 Introduction:

The Aral Sea, once the third largest lake in the world, has lost 90% of its volume. 90% of the Mesopotamian Marshes wetlands have been wiped out. The volume of Russia’s Lake Chany has been cut in half. California’s Tulare Lake – once the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi – has been reduced from 690 square miles to 2 square miles. The Colorado River – the source of water for 40 million people – has been badly overdrawn for a century and could literally run dry in places. In parts of the United States, so much groundwater has been unsustainably withdrawn over the past two centuries that the water table – the depth at which groundwater can be accessed – has fallen a shocking 900 feet in some places. As a result, parts of the US have been sinking for decades: parts of central California have lost 28 feet of elevation due to grossly unsustainable withdrawal of groundwater. The vast freshwater wetlands of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, once a stop-off for tens of millions of migrating birds, have been almost totally wiped out.

As with Lake Chad, none of these catastrophes could have been caused by climate change because each started happening well before there were enough greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to have caused them.

Similarly, up to half of humanity lacks reliable access to clean drinking water. We suspected initially that this could be caused by inadequate amounts of freshwater or even the collapse of freshwater ecosystems. But that wasn’t the case. As discussed in Chapter 1, there are very few places lacking sufficient freshwater. Nearly all of the world’s thirsty go without drinking water due to public policy that does not prioritize human needs like clean water and sanitation, not because of a lack of natural freshwater resources. Moreover, the worldwide drinking water crisis wasn’t caused by climate change, either: as climate change has been accelerating, the portion of humanity without access to adequate drinking water has actually been decreasing. Our case study of Cameroon – where half of all people lack reliable access to drinking water, an estimated 20,000 people die each year from causes that could have been prevented with adequate sanitation, and violent clashes already occur over drinking water – illustrates patterns of poverty and underdevelopment that explain the key drivers of the worldwide drinking water crisis.

In other words, our case studies illustrated a pattern that is true the world over: there is enough freshwater for everyone, and we don’t need to sacrifice natural gems like Lake Chad in order to get it. Now and for the foreseeable future, the greatest threat to freshwater ecosystems and humanity’s access to clean drinking water is not climate change: it’s villains like Paul Biya, the CFA franc, and the IMF. And, as we will see in future issues of Finite, this pattern holds for all manner of our world’s problems. From the extinction crisis to the collapse of the world’s rainforests; from hunger to preventable deaths; the greatest threats to human welfare and the natural world – now and for the foreseeable future – are not climate change.

But if the greatest threat to human welfare and environmental degradation is not climate change, could it be that climate change is not humanity’s most serious problem, but rather an especially severe symptom of a deeper, underlying issue?

Indeed, taken to its logical endpoint, casting climate change as the ultimate villain yields some absurd conclusions. Casting climate change as the ultimate villain implies that we must reverse the collapse of the Yukon River because the cause is climate change, but allow other freshwater ecosystems to collapse – like Lake Chad or the Mespotamian Marshes – because the cause is not climate change. Casting climate change as the ultimate villain implies that we must prevent people from losing access to drinking water due to climate change, but the quarter-to-half of humanity who lacked access to drinking water prior to the acceleration of climate change should continue to go thirsty. Clearly, climate change is not the disease itself, but an especially severe symptom of an underlying disease. This matters because if we don’t correctly understand the problem, we won’t be able to solve it.

A broken political and economic system is the problem

For each of the problems discussed in Issue 1, climate change is not the fundamental problem. Rather, a broken political and economic system – a system that prioritizes profits over all else – underlies each issue. The French installed a dictator in Cameroon in order to protect the profits of French corporations. International financial institutions refuse to forgive loans that have already been repaid several times over, protecting banking profits by perpetuating poverty, underdevelopment, and desertification. The profit motive led colonial governments, their repressive successors, and international financial institutions to impose a broken model of development based on commodity exports.

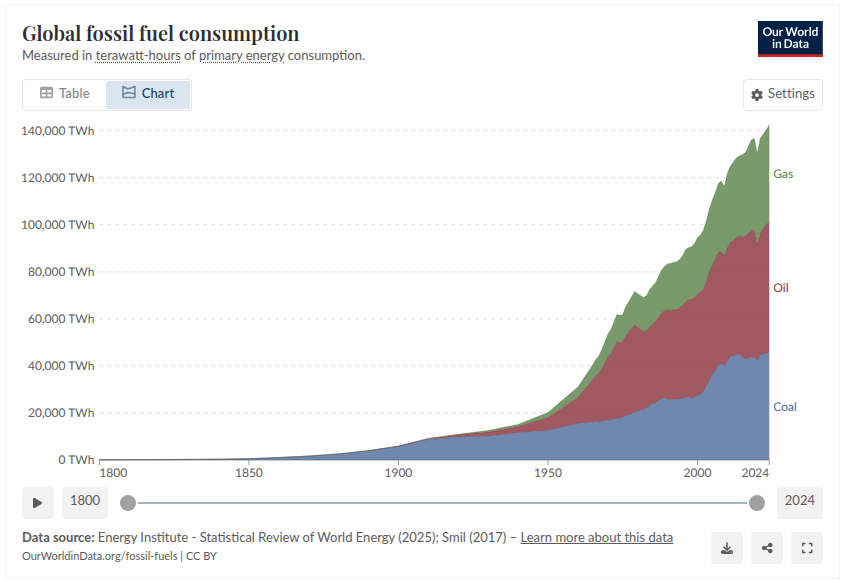

But, a broken political and economic system is also the cause of climate change. The dangers of burning fossil fuels have been widely known since (at least) 1977, when President Carter was warned by his science advisor. But rather than phasing them out, our use of fossil fuels has not merely increased – it’s increased exponentially:

This lunacy could only come to pass in a totally broken system, one that perversely values short-term profits over the future survival of the planet. To this day, governments worldwide subsidize fossil fuel corporations with $5-7 trillion every year. Governments continue to approve new fossil fuel projects (Obama i, ii, iii, iv; Trump’s first term i, ii, iii, iv; Biden i, ii, iii, iv; Trump’s second term so far), investors continue to invest in fossil fuels, and corporations are backing out of pledges to reduce emissions. As though in a suicide pact on behalf of the entire planet, fossil fuel corporations continue to actively impede the transition away from fossil fuels. None of this should be surprising: in our gravely broken system, for a corporation to prioritize anything above maximizing profits is de facto illegal.

Of course, this is not to say that climate change isn’t real, dangerous, or certain to worsen our planet’s many crises. Rather, if we try to stop climate change without fixing our broken political and economic system, the climate movement will continue to flounder. Profit-hungry corporations and their allies in the political system have thwarted every attempt at addressing the climate crisis so far; why should tomorrow be any different? You can’t stop a fever by treating the fever; you have to find and treat the infection causing the fever. Attempting to stop climate change without reforming our profit-driven political and economic system is like trying to treat a symptom while nurturing the disease. Just as poor countries’ debts will never be forgiven without abolishing the profit motive from international financial institutions, neither will corporations, governments, and investors give up fossil fuels until the rest of us abolish the profit motive. The insatiable drive for profits is the underlying cause of every problem in Issue 1, from dictators’ looting their own countries to climate change itself.

____________________________________

Featured Excerpts

Apocalypse Nord (Iss1/Ch4)

These policies led to the Great Depression…what could go wrong? (Iss1/Ch3)

Independence* Day (Iss1/Ch2)

Are we measuring global poverty or intentionally underestimating it? (Iss1/Ch1)

__________

__________

Fighting desertification is urgent for fighting climate change

The other question we have thus far failed to answer: if we can’t stop climate change without stopping desertification of the Sahel, why does the wealthy world show so little concern for the Sahel? The science is terrifying: desertification pumps an astonishing amount of carbon into the atmosphere. Earth’s soils are estimated to hold 2,500 billion tons of carbon, or more than three times as much carbon as is held in the atmosphere. When land is degraded and the vegetation dies, the carbon that had been contained in the soil is released into the atmosphere where it can act as a greenhouse gas: plant roots and the elaborate web of life that includes fungi and unfathomable numbers of microscopic creatures (a single fistful of healthy soil holds more microorganisms than there are people on the earth) die off, decay, and release the carbon that comprised them into the atmosphere. In this way, land degradation is no different from a coal power plant: once in the atmosphere, carbon acts as a greenhouse gas no matter its origin.

Land degradation is a massive contributor to climate change: it’s estimated that a quarter of all carbon emissions generated by humans in the decade 2007-2016 came from land degradation. Simply put, if we cannot get irresponsible land use under control – in the Sahel and beyond – we cannot stop climate change.

What’s more, reversing desertification actually removes carbon from the atmosphere. In Chapter 3, we mentioned the Great Green Wall initiative, which has the goal of completely reversing the degradation of 1 million square kilometers of land at varying stages of desertification. The UN Convention to Combat Desertification estimates that this would sequester a quarter billion tons of carbon. As science fiction technologies of industrial carbon capture are promoted by fossil fuel corporations and breathlessly repeated by a gullible media, we already know how to reverse land degradation at scale. Though not an excuse to delay phasing out fossil fuels, reversing land degradation in the Sahel and beyond has the potential to sequester large amounts of carbon.

Though there are not sufficient data to estimate how much carbon is released into the atmosphere when a square kilometer of the Sahel desertifies, it is clear that allowing the Sahel to continue to desertify is like detonating a carbon bomb into the atmosphere at a time when it is imperative to eliminate carbon emissions. Whether we are moved by the suffering of ordinary Sahelians or not, we must do everything we can to prevent and ultimately reverse desertification, if not simply for our own wellbeing. We cannot afford for the more than 3 million square kilometers of the Sahel to completely desertify.

If land degradation is responsible for up to a quarter of all carbon emissions, then about a quarter of our planning and efforts should be devoted to combating land degradation. Neither the Green New Deal nor the European Green New Deal mention the hotspots of land degradation – the Sahel, South and Central America, and Mongolia, where desertification has wiped entire villages off the map.

In other words, we think that fighting climate change means building hundreds of millions of electric cars and endless fields of wind turbines – not breaking up compacted soil on the other side of the globe. But why? Why do we think about climate change in such an illogical way? Why does the wealthy world not care about the Sahelian desertification crisis?

There are three major reasons.

#1: We consider poverty and environmental policy to be two separate issues. They’re not.

The first reason the wealthy world shows so little concern about the desertification of the Sahel is that we think of poverty and environmental degradation as two separate issues, when they are not. We have seen this in two different ways in Issue 1.

First, poverty and environmental issues have the same root causes: only a totally broken system could prioritize short-term profits over the wellbeing of so many people and the planet.

The second way Issue 1 has illustrated that poverty and environmental policy are two sides of the same coin: no plan to reverse desertification in the Sahel can succeed without addressing poverty and underdevelopment. That’s because poverty and underdevelopment are the direct causes of desertification. As we learned in Chapter 1, desertification is caused by overgrazing, inadequate fallow periods, farming marginal lands, and deforestation. Aside from Paul Biya’s irresponsible timber trade, hunger and desperation are the primary causes of these problems. It is unreasonable to expect people who would go hungry if they left their fields fallow to leave their fields fallow, even if they are creating larger problems long term. It is unreasonable to expect Sahelians to stop diverting water away from Lake Chad to irrigate their crops; it’s either irrigate irresponsibly or go hungry. Much deforestation occurs because ordinary Sahelians lack access to electricity and electrical appliances, and thus firewood is the only option they have for cooking their food; it’s unrealistic to expect people to stop cooking food even if they understand that deforestation will ultimately render their home unlivable. Desertification will not stop unless everyone in the Sahel has enough to eat and electricity to cook with. In other words, halting this ecological catastrophe is impossible without addressing poverty and underdevelopment.

Failing to meet people’s basic needs leads to environmental degradation and worsens climate change. There is no environmentalism without taking care of people’s basic needs. We will not be able to solve our many ecological catastrophes – climate change included – until we understand this.

#2: “Democracy dies in darkness scorching climate change”

The second reason the wealthy world doesn’t care about the desertification of the Sahel is that it simply isn’t reported on by the media.

When a climate scientist and media studies professor teamed up to systematically analyze how the media reports on climate change, they found that 0.1% of articles stated that burning fossil fuels is the source of the greenhouse gases warming the planet. It is no exaggeration to say that mainstream media outlets essentially never report on climate change accurately – 0.1% is a rounding error. While there is no equivalent study analyzing how often desertification is correctly identified as a major cause of climate change, if only one in every thousand articles implicates burning fossil fuels, even fewer must mention land degradation. In other words, even the most conscientious consumer of news in the wealthy world would have no way of learning about the problem.

As we discuss on our from our About page, “Modern media is broken. Even the ostensibly liberal media outlets like the New York Times and Reuters accept fossil fuel money and almost never accurately report on climate change.”

Without independent media – outlets that do not rely on corporate funding – the public will never understand the nature or scale of the problem. But, media outlets need money, and financial independence from corporations means that ordinary people must financially support media outlets that report accurately, or they will not exist. (We are one such outlet, and our only source of funding is subscriber contributions).

#3 Apocalypse Nord

The third reason why the wealthy world is so indifferent to the Sahelian desertification crisis – and why governments of wealthy countries are so obstinately indifferent to climate change – flows naturally from what we covered in Chapter 3: following the advice of mainstream economists leads to catastrophe. Chapter 3 detailed how poor countries’ following the advice of mainstream economists on the best way to develop (commodity exports) experienced a catastrophic recession more severe and significantly longer than the Great Depression. This catastrophe occurred because they followed the advice of mainstream economists. Then, mainstream economists designed a solution to the problem they themselves had created: high levels of debt and structural adjustments. This “solution” made a catastrophic situation even worse. All the while, the East Asian Miracle economies, following policies condemned by mainstream economists as unsound, developed within a single generation – more quickly than any country in the history of the world. Also discussed in Chapter 3, for the Sahel, the folly of mainstream economists was doubly evident because the US had successfully dealt with a nearly identical land degradation crisis – the Dust Bowl – using a set of policies mainstream economists also deemed unsound.

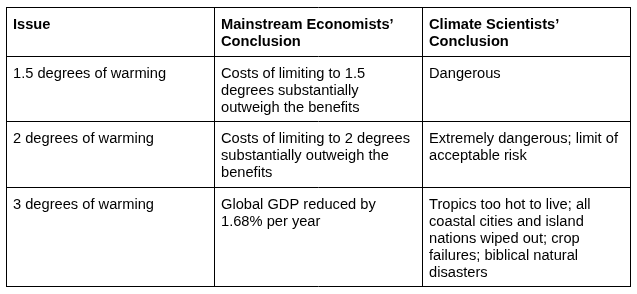

Given this history, you may suspect that following the advice of mainstream economists on climate change (rather than climate scientists) is deeply dangerous. It is. This section is a side-by-side comparison of what mainstream economists versus climate scientists say about climate change. In this section, we use the generally accepted shorthand for warming: e.g., “2 degrees of warming” is shorthand for an average global temperature increase 2 degrees higher than that of the preindustrial world (in 2100, unless otherwise specified).

The founder and leading exponent of climate economics is Yale economist William Nordhaus, the first economist to apply the principles of mainstream economics to climate change. It is no exaggeration to say that Nordhaus is the most important and influential climate economist in the world, and among the most important and influential economists, period. Nordhaus is co-author of the most-read introductory economics textbook, has taught society’s future elites as an Ivy League professor since 1967, and won the 2018 Nobel Prize for Economics.

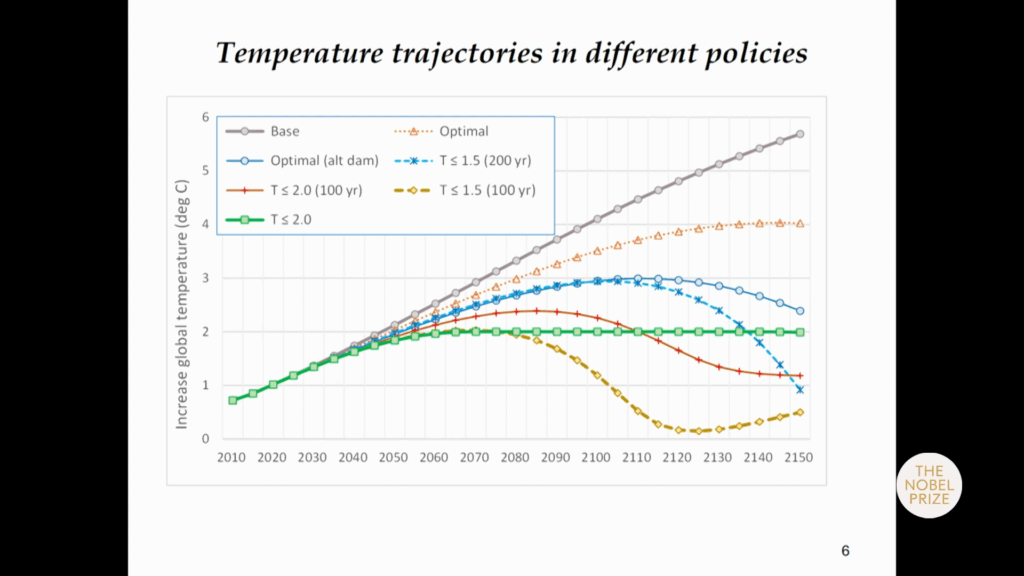

Nordhaus won the Nobel Prize for developing the so-called Integrated Assessment Model (IAM), a process for modeling the economic impacts of climate change that allows for a comparison of the costs of implementing green policy today versus the benefits of preventing the worst effects of climate change for future generations. IAMs have three components. First, an equation calculating economic growth as though there were no climate change. Nordhaus’s models assume 1.9 to 2.1% growth every year. At 2% annual growth, the global economy would approximately double every 36 years and would approximately quadruple by 2100. Second, a damage function: a mathematical equation that estimates the economic costs of climate change to the future economy. Third, an abatement cost function, a mathematical equation that estimates the costs to today’s economy of eliminating the use of fossil fuels.

Nordhaus and other mainstream economists make climate policy recommendations by plugging different variables (future economic growth rates, cost of adapting to climate change, estimates of how quickly the world will warm, etc) into an IAM, then comparing results. The crux of mainstream climate economists’ argument is this: it makes no sense to rapidly phase out fossil fuel use if the costs of doing so today (the abatement cost function) is larger than the costs imposed by climate change in the future (the damage function). Policy makers should aim for an “optimal” warming, wherein fossil fuels are phased out slowly enough that the abatement cost function (the costs of phasing out fossil fuels) will be equal to the damage function (the costs of dealing with climate change in the future).

For example, at 3 degrees of warming, Nordhaus calculates that the damages to the future global economy would only be 1.62% of global output per year. Per Nordhaus’s modeling, such tiny damages are substantially smaller than the abatement cost: in other words, the cost of limiting climate change to 3 degrees is significantly higher than the benefits of doing so. According to these models, limiting warming to 1.5 or 2 degrees is patently absurd: the costs to society of phasing out fossil fuels quickly enough to meet these goals are mammoth compared to the future benefits of doing so. Nordhaus’s argument boils down to: why should people alive today sacrifice so much for a tiny benefit – a tiny benefit that most of us will not even live to see?

Climate scientists, however, consider 2 degrees to be so dangerous that it is the absolute maximum amount of warming we can possibly accept. 1.5 degrees of warming is substantially less dangerous than 2 degrees; 2 degrees is extremely dangerous (as summarized with exhaustive citations at earth.org):

Heatwaves will become more common, more intense, and longer-lasting in a 2C warmer world. Research suggests that the probability of experiencing a heatwave like the one that affected Europe in 2003, causing over 30,000 deaths, will increase from once every 100 years to once every 4 years under 2C of warming.

Regions already prone to high temperatures, such as the Middle East and North Africa, will experience “super heatwaves” with temperatures exceeding 50C (122F). This will make some areas potentially uninhabitable…

Droughts will become more frequent and more severe in many parts of the world. The IPCC projects that the area of global land affected by drought disasters will increase by 50% for 2C compared to 1.5C…Besides affecting water resources, intense and prolonged droughts will decimate food crops and cause high rates of livestock deaths, leading to food insecurity.

While some areas will get drier, others will get more flooded. With 2C of warming, the IPCC estimates that the global population exposed to river flooding will be up to 170% higher compared to a 1.5C scenario…This increase in extreme rainfall events will mean more flash floods and urban flooding…

[T]he proportion of Category 4 and 5 hurricanes will increase by 13% and the average intensity by 5%. [ ] More powerful storms will bring stronger winds, more rainfall and higher storm surges, endangering coastal communities and infrastructure…

[M]ean sea level is projected to rise by 0.46-0.99 meters (1.51-3.25 feet) by 2100 [leading to a] climate refugee crisis driven by the displacement of millions of people living in coastal areas…

Studies suggest that 99% of coral reefs will be lost…

The rate of species extinctions is expected to accelerate, with one study projecting that 18% of insects, 16% of plants, and 8% of vertebrates will lose over half their climatically determined geographic range with 2C of warming.

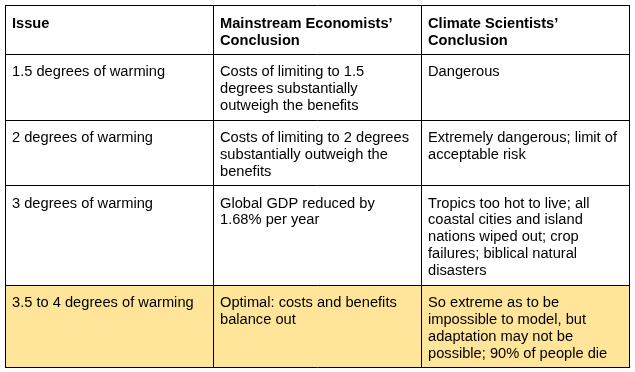

For 3 degrees’ increase, climate scientists model that much of the tropics will become “too hot to live,” oceans will rise enough to wipe out all island nations and coastal cities (including economic powerhouses like New York, London, Hong Kong, and Shanghai), crop failures will dramatically increase, and natural disasters like extreme rainfall and flooding, droughts, wildfires, and hurricanes will increase in frequency and severity.

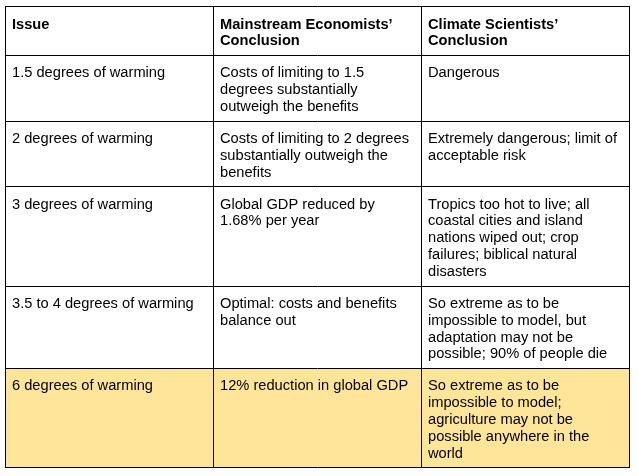

Because so many numbers are being thrown around, let’s use a table to keep track:

You may be wondering: if the economy of every single coastal city, island nation, and tropical region on earth is wiped out; if all those people are displaced from their homes and have nowhere to go; if crop failures and indefatigable natural disasters become commonplace – how can this only lead to a 1.62% dent in global output? Clearly, Nordhaus’s economic models are wrong.

It gets worse. According to Nordhaus’s calculations, the “optimal” warming is 3.5 degrees by 2100, plateauing at 4 degrees thereafter. Here is Nordhaus’s figure from his 2018 Nobel Prize lecture (slide 6):

Per Nordhaus’s calculations, the sacrifices that need to be made today to limit climate change to 3.5 to 4 degrees balance out with the benefits that accrue to future generations.

What do climate scientists think about Nordhaus’s recommendation that 3.5 to 4 degrees is “optimal”? In fact, climate scientists do not even model out past 3 degrees. That’s because the rate of climatic change becomes so extreme that it is impossible to make models or estimates. Climate models are built on data, and data can only be obtained from real-world measurements. Earth has never warmed as quickly as it is warming now, but climate scientists have nonetheless had remarkable success in making accurate climate change predictions by extrapolating from data that do exist. However, warming by 3.5 or 4 degrees is so far beyond the existing dataset that climate scientists do not think it is possible to make predictions with any degree of accuracy. This begs the question: if there are no models for what the climate will look like at 3.5 to 4 degrees of warming, how can Nordhaus and other mainstream economists so confidently predict the impact of 3.5 to 4 degrees of warming on the economy?

While acknowledging the limitations of data and modeling at such extreme amounts of warming, climate scientists have nonetheless speculated about what 4 degrees of warming could look like. When asked to make predictions for 4 degrees of warming by the World Bank, climate scientists argued that accurate prediction was impossible but warned that “there is also no certainty that adaptation to a 4°C world is possible…4°C warming simply must not be allowed to occur.” When asked directly about 4 degrees of warming, one climate scientist said “something like 10 percent of the planet’s population — around half a billion people — will survive if global temperatures rise by 4 C”, and another demurred that “it’s difficult to see how we could accommodate a billion people or even half of that.”

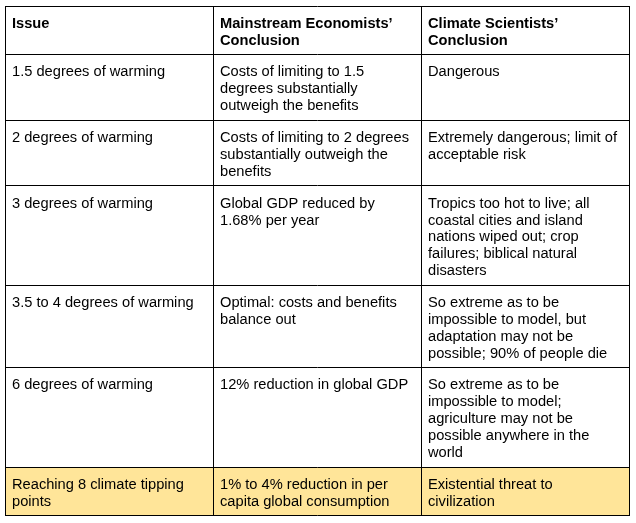

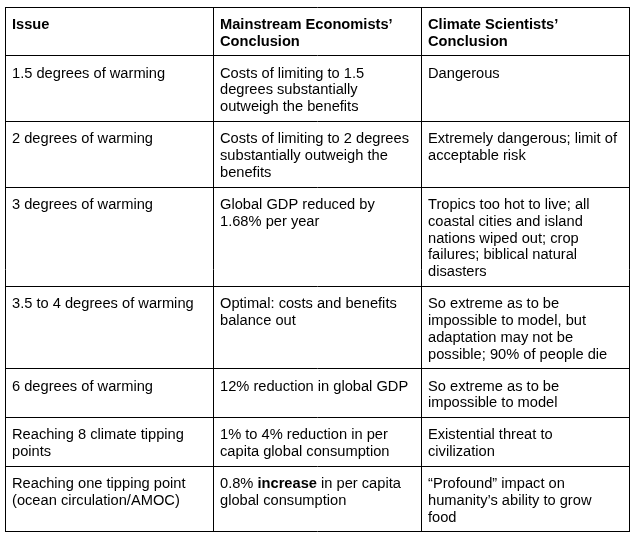

Let’s update the table (new cells in yellow):

Nordhaus estimated that at 6 degrees of warming, global GDP would be reduced by only 8.5% (an estimate he later revised upward to 12%). For climate scientists, 6 degrees of warming would be so extreme that no climate scientist has even modeled it. In the final chapter of Six Degrees (republished in 2020 under the name Our Final Warning), author Mark Lynas attempted to envision in layperson’s terms what the world would look like at 6 degrees of warming. However, Lynas did not find any studies modeling to 6 degrees because there is no way to model such extreme changes. Since no climate models were available, Lynas instead turned to paleoclimatology, a field of geology that uses fossil and geological evidence to reconstruct Earth’s climate before recorded history. Based on evidence from previous periods when Earth was this hot, Lynas speculated that agriculture would be impossible for nearly all of the world, as even Canada and Siberia would be too hot to support farming. (Here are climate scientists grappling with the lack of peer-reviewed studies anticipating catastrophic climate change.)

Another update to our table:

Tipping points, such as the melting of polar ice and the conversion of the Amazon to savannah, are areas of special concern because they have the possibility to abruptly – and irreversibly – lead to an acceleration of climate change. For example, polar ice reflects a great deal of the sun’s heat back into outer space. If the planet warmed enough to wipe out polar ice, climate change would suddenly and irreversibly accelerate because all that extra heat from the sun would no longer be reflected. Climate scientists have identified eight terrifying tipping points and believe that breaching them would be “an existential threat to civilization”. Mainstream economists using IAMs calculated that if humanity passed all eight tipping points identified by climate scientists, per capita global consumption would fall by between 1 and 4%.

Perhaps the most extreme example of the discrepancy between the predictions of mainstream economists and climate scientists is found in the modeling of one tipping point: the slowdown of the massive Atlantic Ocean current (Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, or AMOC) that keeps Europe and North America warm and cools the tropics by circulating huge amounts of warm water north and cool water south. In a paper reviewed by Nordhaus, economists used IAMs to estimate that a slowdown of the AMOC would have a small but beneficial impact on global GDP, and the greater the slowdown, the greater the benefit: a small slowdown would increase global per capita income 0.2 to 0.3%, whereas a near-shutdown would increase global per capita income by 0.8%. The conclusions of climate scientists could not be more different. Climate scientists have estimated that the slowdown of the AMOC would “destabilize the West African monsoon, triggering drought in Africa’s Sahel regions[,] dry the Amazon, disrupt the East Asian monsoon and cause heat to build up in the Southern Ocean, which could accelerate Antarctic ice loss.” It would also lead to lower agricultural productivity in Europe. Rather than beneficial impacts on the global economy, a weakened AMOC would lead to “profound consequences for global food security” due to substantial new challenges of growing food in Europe, Africa, South America, and Asia. Another climate scientist described an AMOC collapse as a “going-out-of-business scenario for European agriculture…You cannot adapt to this.”

We could go on with more examples, but this selection should give you an idea of the gravity of the difference in thinking between mainstream economists and climate scientists – as well as the importance of choosing whom we trust to design climate change policy. The differences between the two camps could scarcely be more extreme, and we will have dramatically different futures depending on whose advice we choose to heed.

How can mainstream economists predict minor dents in global GDP when climate scientists see existential threats to civilization itself? For starters, IAMs literally assume that catastrophes like famines, wars over dwindling resources, or areas of the earth being so hot during summer that they are uninhabitable, can’t happen. In the words of heterodox economists (including Joseph Stiglitz, winner of the 2001 Nobel Prize for Economics), “potentially catastrophic risks are in large measure assumed away in the IAMs”. Heterodox MIT economist Robert Pindyck says the same:

Another major problem with using IAMs to assess climate change policy is that the models ignore the possibility of a catastrophic climate outcome…The bottom line here is that the damage functions used in most IAMs are completely made up, with no theoretical or empirical foundation…IAM-based analysis suggests a level of knowledge and precision that is nonexistent, and allows the modeler to obtain almost any desired result because key inputs can be chosen arbitrarily.

Lest you think these heterodox economists are being unfair, listen to Nordhaus in his own words a year after winning the Nobel Prize, in 2019: “there is at this point no serious evidence” that catastrophic outcomes are possible. No serious evidence? In 2019? It is no exaggeration that mainstream economists are climate change deniers: you can only believe there is no serious evidence of catastrophic outcomes if you disregard climate science itself.

To understand the folly of IAMs better, let’s look at two examples of potential catastrophes that IAMs “assume away.” As explained by climate scientists, IAMs assume no migration: the world’s population distribution in 2100 is assumed to be the same as the population today (emphasis added):

changes in climate hazards can trigger human migration across different regions of the world, which in turn will have effects on land use, water availability, deforestation, desertification, and so on. Also, climate change may eventually make certain areas of the world hostile living places based on temperature rises leading to falling economic output, population decline, social inequality and political crises. However, these complex feedbacks are not adequately expressed in IAMs…population distribution and population density projections from current IAMs are exactly the same for a scenario with sustainable development and a scenario with fossil-fuel intensive development. This is obviously implausible

Total desertification of the Sahel, leading to tens of millions of climate refugees? Not accounted for in IAMs, which assume no net migration out of the Sahel for any reason. Sea level rise swallowing all coastal cities and island nations, displacing billions of people on every continent? Not accounted for in the IAMs, which assume no net migration for any reason. The displacement of 400 million people in the North China Plain as heat waves make the area literally too hot to inhabit? Not accounted for in IAMs, which assume no net migration for any reason. The displacement of up to 3.5 billion people, as much of India, and parts of Nigeria, Sudan, Indonesia, and Pakistan become too hot to inhabit? Not accounted for in IAMs, which assume no net migration for any reason.

In other words, IAMs can, in part, reach fantastically optimistic climate projections because they assume that famines and other disasters don’t happen, and that people can continue living in places that are too hot for human habitation or have been literally swallowed by the sea.

But even these assumptions might seem reasonable alongside the assumption that people don’t need food. Nordhaus has assumed that any economic activity that occurs indoors in “carefully controlled environments” – i.e. with the benefit of modern heating and air conditioning – will be unaffected by climate change. This includes “manufacturing, mining, transportation, communication, finance, insurance, real estate, trade, private sector services, and government services.” Leaving aside the robust research indicating heat does negatively impact supposedly climate-proof sectors, and leaving aside that stoppages to manufacturing and other supposedly climate-proof, air-conditioned processes are already occurring due to extreme heat, this logic literally says that because the market value of economic activity that occurs outside accounts for a small amount of our economy, the economic impacts of climate change are minimal. But one of the activities that must occur outdoors is agriculture(!). Obviously, if agriculture is severely impacted by climate change and there is not enough to eat, the rest of the economy can’t function. If you doubt this is his position, listen to Nordhaus in his own words responding to critics (emphasis added):

Ninety percent of U.S. economic activity has no interactions with the ecological changes [my critics are] concerned about. Agriculture, the part of the economy that is sensitive to climate change, accounts for just 3% of national output. That means there is no way to get a very large effect on the U.S. economy.

No way except for running out of food. This is how – as explained above – when climate scientists predict a “profound” impact on global food security and a “going-out-of-business scenario” for European agriculture if the AMOC shuts down, mainstream economists can predict a positive impact on human welfare.

Conclusion: those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it

The IAM concept is extraordinarily influential. The Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations all used IAMs as a guide to climate policy (instead of IAM they call it the “social cost of carbon”, but it’s the same thing). When researchers submitted freedom of information requests to UK pension funds, they found that 80% were basing investment decisions on IAMs. In covering Nordhaus’ Nobel Prize, the New York Times reported that “the [IAM] approach developed by Professor Nordhaus remains the industry standard.” Even the UN uses IAMs: heterodox economists point out (see footnote 4) that while the UN’s IPCC committee focused on climate science sounds alarm bells, IAMs are used for the IPCC policy recommendations. In other words, from governments to the UN to investors, the rich, powerful, and influential are relying on IAMs to understand climate change and decide how to deal with it.

But we have experience entrusting social policy to mainstream economists: commodity-driven development and structural adjustments were all based on mainstream economic models. They led to a catastrophic recession more severe and longer-lasting than the Great Depression, and people went hungry and died because of this folly. It certainly seems like we are heading toward climate catastrophe by following the policy recommendations of mainstream economists.

Finally, after all this discussion of IAMs and mainstream climate economics, we have uncovered the third major reason why the wealthy world cares so little about desertification: the powerful and influential are using IAMs to understand the problem, with all their totally unrealistic assumptions. The Sahel is expected to warm at 1.5 times the rate of the rest of the world. Though climate scientists can’t accurately model such extreme changes, mainstream economists’ “optimal” warming of 3.5 degrees Celsius at 2100 (and plateauing at 4 degrees thereafter) would almost certainly render the Sahel uninhabitable. This would turn tens of millions of people into climate refugees and pump an unfathomable amount of carbon into the atmosphere. But in an IAM model, nobody becomes a refugee (even if their region becomes unlivable), tipping points are assumed not to happen (or are estimated to have beneficial effects), and famines are assumed not to happen, despite the clear incompatibility of this warming and agriculture. In that mindset, it is no wonder desertification is ignored: no matter how many calculations are made and simulations run, a model that assumes famines, displacement, and tipping points don’t exist will never identify desertification as a problem.

Indifferent to climate change, indifferent to land degradation

In sum, it may seem incredible that the wealthy world does not care about desertification in the Sahel, even out of self-preservation: leaving aside the incredible human suffering and ecological damage, land degradation is responsible for a quarter of humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions, and there is no possibility of averting catastrophic climate change without dealing with it.

Yet there is no real mystery: society’s elites – from elected officials to the mainstream media – have a steadfast indifference to climate change, partly because economists are treated as experts on climate science, and partly because our economic and political system prioritizes profits over all else. Society’s elites are as indifferent to all sources of greenhouse gas emissions, whether fossil fuels or land degradation

So, what should we do?

Clearly, the rich, powerful, and influential trust mainstream economists – and not climate scientists – to understand and deal with climate change. Unfortunately, the twisted logic of mainstream economics has also spilled over into the discourse of how ordinary people ought to contribute to the fight against climate change. Before concluding Issue 1 with a discussion of what is to be done about climate change and desertification, it is crucial that we first recognize this bad advice for what it is.

An ordinary person concerned about climate change would probably do the sensible thing and Google the problem. We performed two Google searches: “how to contribute to the fight against climate change“ and “how can governments help with climate change?” in order to address the information a concerned layperson is most likely to encounter. Unfortunately, these search results send well-intentioned people toward actions that are, at best, ineffective distractions from what actually needs to be done.

Nudging us over a cliff

A concerned citizen might approach an elected official with suggestions from the top three results of a Google search for “how can governments help with climate change?”. These results all reflect the political system’s reliance on economists as climate experts. The top result, from the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, counsels that above all, “economists across the political spectrum agree that a flexible, market-based approach is the most cost-effective way to reduce emissions, and should be a centerpiece of a comprehensive climate strategy.” The top recommendations from the Council on Foreign Relations are carbon taxes and cap and trade, two policies wherein the free market is largely left alone, but governments attempt to nudge corporations in a greener direction by making it more expensive to burn fossil fuels. (The Council on Foreign Relations highlights the completely toothless Paris Agreement as a success, further demonstrating how out of touch these “experts” are with reality.) The consulting firm EY begins with bold goals that would be at home in a Sunshine Movement press release, like “transformation of energy and industrial systems”; however, the policies it ultimately recommends are milquetoas. For example, they recommend a “stick and carrot approach, including green taxes on harmful environmental activities, tighter regulations, and new environmental standards and certification [ ] – including tax rebates for meeting these standards…[and s]ubsidies and tax rebates.” The first problem EY lists as an obstacle to action is “[r]egulatory and policy uncertainty” which “reduces project viability, investment, private sector interest and innovation.”

In short, the recommendations are for business as usual, with nudges from governments to encourage corporations to do the right things: nudges like taxing carbon emissions to make burning fossil fuels more expensive, offering tax rebates for meeting energy efficiency standards, and use of regulations to discourage harmful behavior. Though the connection is beyond the scope of what we can cover here, these are, by and large, the policy recommendations of mainstream economists like Nordhaus.

This mainstream economist-approved approach to fighting climate change cannot possibly work. Fossil fuel corporations discovered the danger of climate change as early as the 1950s, but actively deceived the public to protect their profits. Behind closed doors, fossil fuel executives admit that – even at this critical juncture – they are actively working to sabotage a transition away from fossil fuels. Corporations writ large have not made any meaningful changes to address climate change: just compare what they say in public to what they actually do (h/t). In other words, corporate investors and managers have chosen to protect short-term profits over the ability of humans to survive on earth. If the threat of wiping out human civilization isn’t enough incentive to change corporations’ behavior, why should a tax credit? If corporations can break the law – either wholly without consequences or by paying fines substantially less than the profits gained from that illegal behavior – why would new regulations even be effective? The idea that corporations should be further subsidized is particularly ridiculous; American corporations receive hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies each year, with fossil fuel corporations taking a large share. Why should green subsidies be so powerful when corporations already have a menu of other subsidies to choose from?

Land degradation is conspicuously absent from these lists, even though it is the cause of a quarter of humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions. It certainly seems that the authors of these lists are more interested in protecting our current political and economic system than the planet. Remember, to reverse desertification in the Sahel would require addressing poverty – so Sahelians aren’t forced to take environmentally destructive actions in order to survive – and electrification – so Sahelians aren’t reliant on firewood to cook. But what would be necessary to accomplish these goals? The debts of Sahelian countries must be forgiven, but doing so would require eliminating the profit motive from international financial institutions. In other words, the entire system of international finance would have to cease to exist in its present form. Building out electricity and water infrastructure in rural Sahel is not, and may never be, profitable. To reverse desertification thus also requires abolishing the profit motive from infrastructure. Unwilling to consider a fundamental rethinking of our political and economic systems, mainstream economists have ruled out all but a set of recommendations that would rather usher in an end to the world than an end to free market capitalism.

The pointless busywork distracting us from the necessary systemic changes

After contacting an elected official, a concerned citizen might try our second Google search, “how to contribute to the fight against climate change”, to do their part to fight climate change. The top four results were very similar lists. The UN’s “10 Ways You Can Help Fight the Climate Crisis” includes “tweak your diet”, “shop local”, and don’t waste food. Global Citizen’s list “4 Ways You Can Fight Climate Change and Help the Environment” includes reducing consumption, not using straws, and opting for reusable grocery bags. On its “What You Can Do About Climate Change” page, the US Environmental Protection Agency recommends the installation of “energy- and water-efficient appliances and fixtures.” The Goldman Environmental Prize “Six Ways to Contribute to a More Sustainable and Resilient World,” includes “reduce, reuse, recycle”. Aside from the apolitical EPA, all lists recommend continuing to pressure corporations and politicians to act, using the same set of tactics that have a proven track record of failure.

From these lists, it is easy to see the logic of the free market overpowering how we think about climate change. In mainstream economics, there are no people who care for each other or the common good; there are only greedy individuals, each selfishly pursuing their self-interest. This underlying assumption of economics was succinctly expressed by Adam Smith, the father of economics, in 1776:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages. Nobody but a beggar chooses to depend chiefly upon the benevolence of his fellow-citizens.

When this type of thinking infects how we think about climate change, we get stuck on highly individualized solutions, rather than thinking of how we can – and must – work together. According to this logic, each of us as individual consumers can make responsible decisions, like recycling or eating more climate-consciously, and each of us as individual voters can incorporate climate change into our decision-making as we choose among the candidates and referenda that appear on our ballots. By this logic, change occurs when thousands, then millions, and then billions of us make responsible individual consumption decisions.

But following these suggestions cannot possibly work, whether for phasing out fossil fuels or addressing land degradation. For example, if all Americans suddenly resolved to stop driving, only about half of Americans would actually succeed: forgoing cars is an option only for the fraction of Americans with some access to public transit. Moreover, the government would continue to deeply subsidize fossil fuels. Ironically, polling consistently indicates that large majorities of people in wealthy countries want their governments to take a more active role in fighting climate change, yet the options on voters’ ballots by and large only contain politicians indifferent to climate change (e.g., Obama, Pelosi).

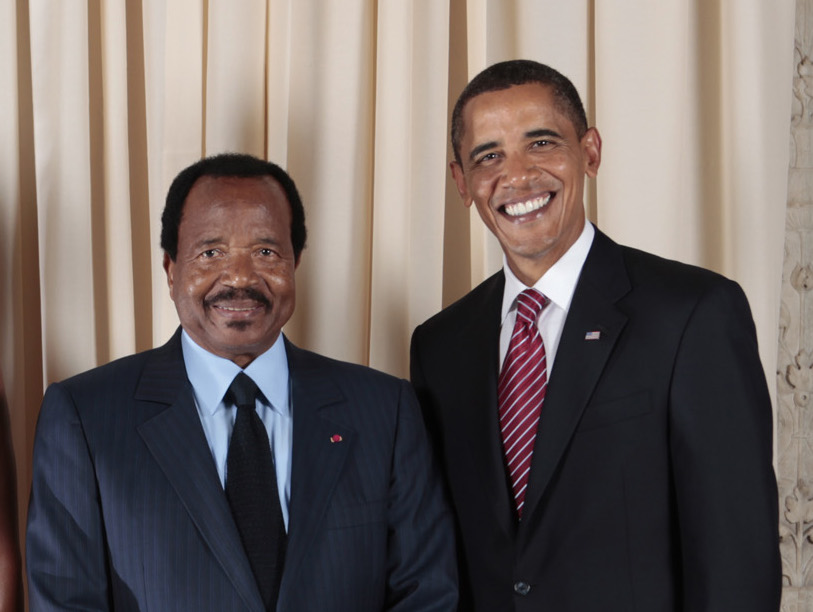

Similarly, if all Americans suddenly decided to take action on Sahelian desertification, what could they actually do as individual consumers or voters? Individual consumers have no opportunity to influence the Sahelian agricultural system by refusing to buy products that contribute to desertification because those products are sold locally or consumed by the producers themselves and never on the world market. Similarly, no American politician has a position on desertification; individual voters thus have no opportunity to force the political system to respond by voting. A major impediment to Cameroon’s development has been its dictators, but Republicans and Democrats have both been friends of Cameroon’s dictators:

The solutions to desertification – restoring Cameroon’s public agricultural bank, reversing the sale of the electrical utility, infrastructure investments – require massive reforms to the way our world works, from international finance and development, to wealthy country governments’ support of dictators and lack of interest in land degradation. When we limit our thinking to personal choices – as in the recommendations for voting, changing our diet, forgoing straws, buying reusable bags, recycling – we are left with a menu of choices that cannot meaningfully contribute to reversing land degradation or phasing out fossil fuels. This type of thinking prevents us from seeing the immense, structural changes that are actually necessary. Climate change isn’t the result of billions of individuals making poor choices like forgetting to vote or using straws. The problem lies in the broken systems, not how any individual acts within those broken systems. As long as we focus on individual actions, we will not be able to see – and will thus be unable to solve – the systemic problems that are actually leading us to climate catastrophe.

Sign up here to be notified when a new issue of Finite is published (4 emails/year)

Hopefully inoculated against bad ideas, we will conclude Issue 1 with a different way of thinking about these problems.

Conclusion: Reasons for optimism

Despite the varied challenges and villains presented in Issue 1, there are many reasons to believe that we can and will solve all these problems.

First, although no decision you can make as an individual consumer or voter will ever make any difference alone, you are not powerless. You can contribute to a movement for change. In Issue 3, we will take a deep dive exploring how individuals can meaningfully contribute to a movement for sweeping social change, offering proven methods that have worked before. But you don’t need to wait for Issue 3, because Issue 1 has a powerful example to learn from: UPC, the organization behind the Cameroonian independence movement we met in Chapter 2 and Bonus Chapter 1. In working for a better future through independence and reunification, UPC took on the might of the French empire and Cameroon’s elites, and nearly won.

UPC was made up of ordinary people. UPC members met in local chapters. When there were too many local chapters to meaningfully coordinate activities, UPC developed regional committees to help local chapters coordinate. Ruben Um Nyobe wasn’t an expert on anything: he was an ordinary person who was chosen democratically by UPC members to lead them. UPC’s only funding came via individual members – some of the poorest people on earth – paying small membership dues.

As we’ll see in Issue 3, this model – the civic organization model of ordinary people contributing time and money as able to advance a cause – is the only model that works. This is not “doing what you can” as an individual consumer or voter. It is a fundamentally different approach that accepts that no matter how many people are trying to do the right thing, individuals working as individuals cannot effect change, but can only do so through collective action. We need a UPC for climate change, for desertification, for so many issues.

Another key lesson comes from the French Communist Party. As we saw in Bonus Chapter 2, UPC would never have been founded were it not for the French Communists. Once founded, the French Communists supported UPC at crucial moments: Um Nyobe would never have testified in front of the UN without their help. The French Communists recognized that a typical French person had more in common with a typical Cameroonian person than they did with the French corporations and French elites being enriched by colonization. This idea is called internationalism, and you, too, have more in common with a Sahelian struggling with day-to-day life than you do with the political and economic elites of your own country. A typical Cameroonian has more in common with you than she does with Paul Biya. Why not work together on common interests and fight common enemies together? We all share one atmosphere, so desertification is urgent whether or not you live in the Sahel.

Indeed, movements led by ordinary people have already forced dramatic changes to the broken systems responsible for the problems outlined in Issue 1. Structural adjustments are no longer forced onto poor countries after a worldwide movement known as Jubilee 2000 forced the World Bank and IMF to abandon structural adjustments. Additionally, as a result of that movement, hundreds of billions of dollars of poor countries’ debts were forgiven. This movement didn’t win because they had truth on their side – if that were enough, we’d live in a utopia. Many economists and other experts still believe that structural adjustments are good policies, despite widespread evidence to the contrary in poor countries around the world. Rather, they won because they fought back. They could have done so much more with more people contributing. The good guys can win, but they need your help.

All debts of poor countries should be fully forgiven. Remember, the principals of these debts have already been repaid a few times over, but can never be paid back in full due to compounding interest rates. It is crucial to recognize that the institutions primarily responsible for these problems – the IMF and World Bank – are controlled by the governments of rich countries. In particular, the bulk of the budget and control of both institutions comes from the United States. Reforming the IMF and World Bank isn’t merely a movement that you can contribute to; as a citizen of the country that dominates these institutions, these monsters cannot be stopped without your help. Jubilee USA is modelled on Jubilee 2000. As discussed earlier in this chapter, there is no possibility of stopping climate change without stopping desertification; however, there is no possibility of stopping desertification without meeting people’s basic needs. Contributing to Jubilee USA might not seem like a way to fight climate change, but it is.

Another reason for optimism is that most people want to fix these problems. Cameroon is a microcosm of climate change. From the Cameroonian elite’s plundering of all aspects of the economy and profiting from deforestation, to the bankers that made and own Cameroon’s loans, to the bankers in the IMF that forced Cameroon to adopt structural adjustments – the villains are all wealthy, and everyone else is just making the best of a bad situation. We have no doubt that the vast majority of people in wealthy countries like the US would be happy to pay for all of the water infrastructure and anti-desertification needs of Cameroon if they understood the situation. This is particularly true because large majorities of people in rich countries express in surveys that they want their governments to take a more active role in fighting climate change. Since land degradation is the source of up to a quarter of all carbon emissions, addressing the underlying causes of Sahelian desertification would certainly fit the bill. Though governments of rich countries have not acted on climate change in the way their voters want, the fact that large majorities of people want to fix these problems is reason for optimism.

A final reason for optimism is an idea we’ve returned to a few times now: the American New Deal successfully solved a basically identical problem in the Dust Bowl. A proven model already exists. Moreover, the necessary labor and much of the expertise already exists in the Sahel: the Great Green Wall Initiative has been underway since 2005, and its limited successes prove that the efforts can work. The proven successes of the Great Green Wall could be dramatically expanded if sufficient funding were available. As we mentioned in Chapter 3, it’s estimated that to fully reverse desertification of the Great Green Wall focus area by 2030 – approximately one-third of the total land area of the Sahel – would only cost $3.6 to $4.3 billion per year. To illustrate how small this is, the US alone spends nearly a trillion dollars per year on defense, and much of that money is clearly wasted. We already know what to do; it’s just a matter of finding the money to do it. Unfortunately, due to structural adjustments and the realities of currencies and sovereign debt, it is impossible for Cameroon or other Sahelian countries to finance a Sahelian New Deal. The rest of us need to find a way to finance a Sahelian New Deal, even if simply out of self-interest, to prevent the far-reaching consequences of a complete desertification of the Sahel. This must be done with the planning and involvement of those affected, and must bypass the many dictators that colonizers installed throughout the Sahel.

Though Lake Chad’s collapse is a catastrophe, it could be a lot worse. Fishermen still pull 60,000 to 120,000 tons of fish from Lake Chad each year. Invasive grasses are interfering with the Lake’s normal ecology, forming dense mats at the surface of the lake. But no fish have gone extinct due to Lake Chad’s unique characteristics. In other words, if desertification is reversed and diversions reduced, Lake Chad has the potential to restore itself.

Our world’s political and economic elites won’t solve these problems. If you remember one thing from Issue 1, remember that UPC took on the might of the French Empire and were just weeks away from a decisive win. If UPC could accomplish this on nothing more than the tiny membership dues of some of the poorest people on earth and the spare time of those dues-paying members, we can surely solve all of these problems, but only if we organize ourselves and fight back effectively.

The section comparing mainstream economists’ predictions about climate change with those of climate scientists is excerpted here.